With and Against the Archive:

Reflecting on Twelve Marital Deeds of Romani Slaves from Wallachia

The history of Romani slavery on the territory of current day Romania remains largely overlooked, its traces being buried in fragmented archives. Scholars like Adrian-Nicolae Furtună made significant progress in collecting, translating, and interpreting these records, yet more efforts are needed for bringing archival information to public awareness. Among the historical documents uncovered by Furtună, marital deeds offer a rare glimpse into the personal lives of enslaved Roma, revealing both the constraints and agency within the institution of slavery. Through a close analysis of twelve such documents, I examine how primary sources reveal, and obscure, the realities of marriage among enslaved Roma in Wallachia. Some slaves would marry in secret, without their masters’ approval. Others gained acceptance for their union. There were also cases of free people marrying Romani slaves, sometimes having to give up their freedom in the process. Was love more important? Were there other sides to such decisions? The documents from the Roma Enslavement Archive show various answers to these questions. Furthermore, using Saidiya Hartman’s method of critical fabulation, I consider how the gaps in these records might be filled, questioning not only what we can recover, but also why we seek to reconstruct what history has left unsaid.

Keywords: Romani slavery, Wallachia, marital deeds, critical fabulation

Introduction

Romani people have an often overlooked past in Wallachia and Moldova, historical principalities of Romania. They were slaves, treated like objects that belonged to landlords, courts, and monasteries.¹ Few Romanians are aware of this, as the topic is still a taboo in the country, yet it counts for a large proportion of the land’s history. The first recorded instance of Romani slavery in the Romanian territories dates back to 1385, when Lord Dan I donated 40 adobes of slaves to Tismana Monastery.² For nearly five centuries, until 1856, the institution of slavery shaped the lives of Romani people in the principalities of Wallachia and Moldova, leaving behind fragmented and often inaccessible records.³ The challenge of interpreting remaining accounts is complicated by archival gaps, illegible documents, and the absence of voices from those who lived through enslavement. Exploring ongoing efforts to reconstruct silenced histories of Romani slavery, I focus on Adrian-Nicolae Furtună’s contributions to making archival documents more accessible, taking some of these accounts as a case study.

The Roma Enslavement Archive

A promising project by the National Centre of Roma Culture in Romania is forming an online archive on the slavery of Romani people in Wallachia and Moldova.⁴ In December 2016, the database was updated with 225 additional documents from various historical archives around the country.⁵ These amount to 2183 photographs, which should be available online.⁶ The website, however, is no longer functional.⁷ Only a part of its pages are still retrievable through WayBackMachine, a digital archive that stores older versions of webpages.⁸ Fortunately, Adrian-Nicolae Furtună, prominent scholar of Romani studies, put together a collection of historical documents from the temporarily lost digital archive.⁹ Printed in 300 copies, his book was freely distributed to the public with the support of the National Center of Roma Culture.¹⁰ It informs its readers about Romania’s history concerning slavery, and it is also available online in a bilingual edition, in both Romanian and English.¹¹

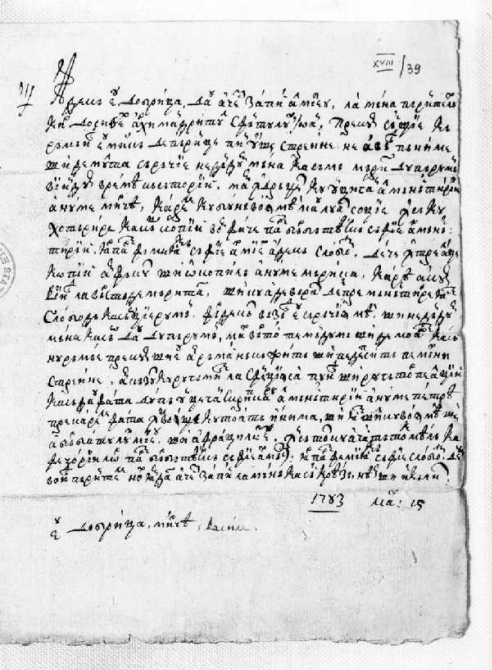

In this work, Furtună alongside two translators made the interpretative groundwork for 33 archival documents.¹² Through extensive introductory sections, the author contextualized several deeds, which are arranged chronologically into three chapters: sales or donations of Romani children, marriages, and requests for emancipation.¹³ The first category consists of 16 documents, the second of 12, and the last one of 4, followed by an extract on a slave’s runaway from his master. Each document appears in three formats: images of the original cyrillic writing, the translation of the legible text from the older Romanian into the current Latin alphabet, and a translation into English. The translations in Romanian and English done by Dr. Ștefan Berechet and Gabriela Murgescu, respectively, are accessible for me. I cannot, however, decipher the original archival document. Therefore, my research is grounded in the interpretative work of Dr. Ștefan Berechet.

In one of the introductory sections, Furtună analyzes the first 16 documents of the collection.¹⁴ He traces the customs surrounding donations and sales of Romani children, in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, in Wallachia.¹⁵ Sons and daughters were separated from their parents and sold to other slave owners. In Moldova, this practice was officially banned in 1766, as it was eventually considered inhumane, yet an abolition of the practice in Wallachia was not officially recorded, from what is currently known.¹⁶ Furtună does not closely analyze the documents in the other chapters, those on marriages, emancipation, and the runaway case.

Taking Furtună’s approach on the first 16 documents as an example, I turn to the marital deeds for a case study. I analyze what the writings can say about marriage regulations for both slaves and free people marrying slaves. This also involves a reflection on what the archive cannot tell, what is no longer legible or what is not mentioned at all. Using the method of critical fabulation of Saidiya Hartman, I ponder on what could potentially fill in these gaps.

Critical Fabulation as a Method

In thinking about the archives on slavery and its victims, Saidiya Hartman notices the limitations that factual records have in showing the stories and voices of those who are long dead.¹⁷ No account of the past can be complete, as there are gaps in what a primary source can tell about times gone and its people. According to Hartman, critical fabulation “is a history of an unrecoverable past; it is a narrative of what might have been or could have been; it is a history written with and against the archive.”¹⁸ Therefore, the practice she proposes constructs plausible stories that fill in absences from the archive, but are outlined by the presences in available sources.

Marital Deeds from Wallachia

The twelve marital deeds from Furtună’s booklet showcase customs and agreements surrounding slave marriages from 1665 to 1841, in Wallachia. It is worth noting that each contains gaps, whether due to illegible words, unclear phrases, or missing relevant details, such as the ages of the husband and wife. From what is available to me, I outline the contents of this document collection, highlighting some of their implications. Using critical fabulation, I then focus on the story of Maria and Neculae, which I reflect on based on findings from all marital deeds.

General Description

The first document, from December 22, 1665, is an agreement on the marriage of two slaves, one from a lord’s court, another from a monastery.¹⁹ It shows that slaves from different types of owners were (at least sometimes) allowed to live together. In this case, the partner from the court would move to the monastery, while the court would receive another slave in return. The union between the two Roma people depended on the willingness of their masters. While agreements were typically recorded, the possibility of owners forbidding their slaves' marriage is only implied by the necessity of such agreements.

The second document, from February 1, 1674, concerns free Romanian Dina taking Fiera for a husband, Romani slave belonging to a monastery.²⁰ They got married in secret, then returned to the monastery, where Dina gave away her freedom. Therefore, Romanians could become slaves too, through marriage. Only love for Fiera was mentioned as a cause, but it was common for free, yet poor women to marry into slavery, as the context of other marital deeds shows. Furthermore, the written confession is transcribed by a hieromonk on behalf of Dina, who probably dictated the words, not knowing how to write. This is the case for all other documents that contain declarations from lay people involved in slave marriages. Their voices are heard only through an intermediary.

The third document is from May 15, 1783, an account of the orphan Dobrița, a free, but poor Romanian.²¹ “When the time to get married came,” she became the wife of Mircea, monastery slave, under the agreement that their sons would be slaves too, and the daughters free.²² She might have had her liberty, but being poor as well, Dobrița’s daughter could not afford marrying a free Romanian. Therefore, she married slave Petrea.²³ There seems to be a variation in the agreements regarding the children of such mixed marriages, as it is exemplified by other deeds as well, like the fifth, eighth, and ninth documents.

The fourth document is from September 26, 1792, when Maria, another free, but poor woman, marries slave Neculae from a monastery.²⁴ Her status after this union is unclear, so is that of their children.²⁵ I will return to this deed in the following section, that on critical fabulation.

The fifth document is from May 13, 1794, stating that free Zamfira marries slave Soare and becomes a slave too, a fate destined for their children as well.²⁶ The economic status of Zamfira is not mentioned here.

The sixth document is from November 17, 1800, attesting that Chiva, impoverished and estranged from others, asked to work among the slaves of a monastery, then to marry Anastase, therefore giving up her freedom and belonging to the monastery too.²⁷

The seventh document is from April 5, 1809, telling about a slave marriage done in secret between the two slaves, Ioana and Frățilă, each from a different monastery. It is recorded that they are forgiven by their masters, who make arrangements of exchanging slaves in order to keep the couple together. Nițu, Ioana’s son from another marriage is taken away from her.²⁸ Though they are eventually allowed to marry, Ioana and Frățilă do not seem to have a say in the fate of Nițu. What happens to these people is ultimately the decision of their masters.

The eighth deed is from 1815, attesting that free Smaranda fell in love with slave Danu of a monastery, then got married with the consent of the priest.²⁹ Smaranda and future children would from then on belong to the monastery, but it is not clear if this gives them the status of slaves or if there were any practical differences between “belonging to the monastery” and “being a slave of the monastery.”³⁰

The ninth document is from September 10, 1819, telling of a widowed, poor woman with two daughters, Rada and Maria, who choose to marry slaves Costea and Ioniță, respectively.³¹ For the first time in this series of deeds, the age of the wives is mentioned: Rada is 13 years old, while Maria is 12 years old.³² Perhaps all other women had to marry at this age. In this special case, the girls keep their freedom, and so do their daughters, while their sons gain slave status.³³ It might be that the free daughters of Rada and Maria would also have to marry slaves, due to poverty, like the third document exemplifies.³⁴

The tenth deed is from June 24, 1820, when a free man gets a slave from a monastery as his wife, for which he has to give a regular payment to the clergy.³⁵ It is the only document from the collection that indicates a free man married a slave woman.

The eleventh and twelfth deeds, from August 5, 1832, and July 24, 1841, respectively, are less clear on their implications. They both concern marriages between Romani slaves.³⁶

Critical Fabulation

Maria’s finger is dirty with ink—from the deed she signed today, binding her to a new life. She spoke the words herself, and there is no taking them back: “I will obey the holy Monastery and my husband. Nobody shall judge me, because I do so willingly and without coercion.”³⁷ Mihaiu wrote everything down for her. He is one of the singers from the monastery. She just had to press her inky digit on the written deed. No other witness signed it. And so, on September 26, Maria’s new status was recorded: wife of Neculae, future mother, and slave to the holy Monastery.

Neculae belonged to the clergy—he was their property. Skinning was his trade, the craft he had learned since childhood. Saint John Monastery provided food and shelter; it kept him alive. While masters were forbidden from killing their slaves, painful punishments were common for those who disobeyed. Did Maria know what she was getting into? She said she loves Neculae. They kept meeting in the summer, here, in Bucharest. Father Costandin agreed to marry them. Not all unions like theirs received a blessing; some lovers ran away and wed in secret. Fortunately, this was not their fate.

Maria’s belly feels heavy as she goes about her daily chores. “All our children shall belong to the holy Monastery…”³⁸—she spoke those words, too. What could she do? Their child will be born soon. Maria may have surrendered her own freedom, but the little one had no say in the matter. Would it be a boy, destined to become a skinner like his father? Or a girl, tasked with the same chores Maria now performed? Would they remain a family, or would the child be traded away? So much was uncertain. Yet, life with Neculae at the monastery was the best Maria could hope for—for both herself and her child.

She had to get married anyway, it was the age to do so. No Romanian would have taken her as a wife. She was so poor… Maybe Maria fears for her child, for the liberties she had to give away, but she did not say this on paper. People may talk, but so they always do. Other impoverished young women also became slaves like Maria. Maybe it is to be admired even, that they saw beyond the status of their husbands. They saw humanity where others saw mere property.

At least, this is what I imagine, more than 200 years after the deed was written. As another Maria, also from Bucharest, I tried to put myself in my namesake’s shoes. But the truth is, I do not know if she even wore shoes. I reflected on each of my sentences with the archive at hand, but against its dry, reductive format. The above paragraphs aim to give space for Maria’s potential thoughts and concerns to emerge, offering the readers a more accessible and vivid portrayal of her humanity—her hopes, her fears, and the quiet resistance within her. I believe she had more thoughts than what was captured in the deed she signed, though I hesitate to speculate on the nature of her fears and hopes—only that they most likely existed.

Discussion

As I end this document analysis, I cannot help but wonder: Why do we seek to complete the incomplete, to add to what is left unsaid by history? What is the function of critical fabulation, of plausible historical re-enactments? Perhaps we are just curious, willing to imagine all possible alternatives for what could have been happening in a past that left (almost) no traces. Or maybe we seek higher goals in tracing such potential narratives, attempting to do justice (whatever that entails) to lives or practices which seem worth remembering. In filling these gaps, however, we must also acknowledge the ethical weight of our interpretations. Are we giving voice to the silenced, or are we reshaping their stories to fit our own understanding? The tension between recovering lost histories and respecting the limits of archival evidence is a delicate one. Still, by engaging with these fragments, even with their absences and uncertainties, we take a step toward recognizing the humanity of those whose lives were once reduced to property and whose experiences remain largely untold.

Lastly, further research is needed to deepen our understanding of the social, legal, and personal dimensions of Romani slavery, as well as the ways in which these histories continue to shape present-day realities. Another work of Furtună, together with Claudiu Victor Turcitu, archivist and historian, is Roma Slavery and the Places of Memory: Album of Social History.³⁹ This entails a larger collection of historical documents from the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, translated in both Romanian and English.⁴⁰ Further contextualization and interpretations would benefit this collection of primary sources, which was also freely distributed to the public, with the help of the Department for Interethnic Relations of the Romanian Government. For the purpose of this essay, however, I could focus only on Furtună’s previous work.

Conclusion

The twelve marital deeds examined in this study offer a rare glimpse into the lived realities of Romani slavery in Wallachia. These documents reveal more than just legal agreements; they expose the complex intersections of love, survival, and systemic oppression that shaped the lives of enslaved individuals. The recurring theme of free women relinquishing their freedom to marry enslaved men underscores the limited choices available to impoverished individuals, particularly women, whose status and futures were often determined by economic necessity rather than personal agency. The fates of their children (some free, some enslaved, often determined by gender) further illustrate the deeply ingrained structures of inequality that dictated social mobility and familial bonds. Even if born free due to special agreements, the daughters of slaves would often have to marry with slaves too, due to their poverty.

Beyond the immediate details of each case, these deeds raise broader questions about autonomy, consent, and the meaning of freedom within an institution designed to deny it. The marriages recorded in these documents challenge simplistic narratives of slavery, revealing instances of resistance, adaptation, and negotiation within an oppressive system. At the same time, the gaps and uncertainties within these records highlight the limitations of the archive itself. We can read what was officially documented, but the emotions, struggles, and unrecorded acts of defiance remain lost to history.

In reflecting on Maria’s story, I’ve sought to weave together the silences of the archive with the complexities of her lived experience. The official records—cold and reductive—offer little more than a snapshot of her existence, yet they fail to capture the depth of her humanity, her inner world, and the weight of the choices she faced. Through critical fabulation, I have attempted to imagine what might have been hidden in those silences: her thoughts, her fears, and her hopes, all of which remain beyond the grasp of the historical document. By doing so, I hope to provide a fuller, more accessible portrayal of Maria—not just as a name on a deed, but as a person with a life, a story that transcends the limitations of the written word. In this way, her story is not just about the past, but also about the ways in which we, as readers and historians, engage with memory, archives, and the histories that remain unspoken.

Endnotes

Marton Rovid, “From tackling antigypsyism to remedying racial injustice,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45, no. 9 (2022): 1745.

Adrian-Nicolae Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească: Fragmente de istorie socială (Vânzări de copii/donații, căsătorii, cereri de dezrobire) (National Center of Roma Culture, 2019), 12-13 (for the Romanian version), 36 (for the English version).

Adrian-Nicolae Furtună, Anca Parvulescu, and Manuela Boatcă, “Three Documents from the Archive of Roma Enslavement,” PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 139, no. 5 (2024): 872–76. https://doi.org/10.1632/S0030812924000701.

“Sclavia Romilor în Țările Române (Roma Slavery in the Romanian Principalities),” The National Center of Roma Culture, https://web.archive.org/web/20170616230112/http://ro.sclavia.romilor.ro/.

“Sclavia Romilor în Țările Române (Roma Slavery in the Romanian Principalities).”

“Sclavia Romilor în Țările Române (Roma Slavery in the Romanian Principalities).”

Simply accessing http://ro.sclavia.romilor.ro/ does not lead to any results.

“Sclavia Romilor în Țările Române (Roma Slavery in the Romanian Principalities).”

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 26-33 (for the Romanian version), 45-52 (for the English version).

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 26-33 (for the Romanian version), 45-52 (for the English version).

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 26-33 (for the Romanian version), 45-52 (for the English version).

Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-1.

Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” 12.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 98.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 101.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 104.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 104.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 104.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 106.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 106.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 108.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 111.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 115.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 117.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 117.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 120.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 120.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 120.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 104.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească 125.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 127, 131.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 106.

Furtună, Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească, 106.

Adrian-Nicolae Furtună, and Claudiu Victor Turcitu, Sclavia romilor și locurile memoriei: Album de istorie socială (Dykhta! Publishing House, 2021).

Furtună, and Turcitu, Sclavia romilor și locurile memoriei.

Bibliography

Achim, Viorel. Țiganii în istoria României. Editura enciclopedică, 1998.

Beck, Sam. “The origins of Gypsy slavery in Romania.” Dialectical Anthropology (1989): 53-61.

Furtună, Adrian-Nicolae. Sclavia romilor în Țara Românească: Fragmente de istorie socială (Vânzări de copii/donații, căsătorii, cereri de dezrobire). National Center of Roma Culture, 2019.

Furtună, Adrian-Nicolae, and Claudiu Victor Turcitu. Sclavia romilor și locurile memoriei: Album de istorie socială. Dykhta! Publishing House, 2021.

Furtună, Adrian-Nicolae, Anca Parvulescu, and Manuela Boatcă. “Three Documents from the Archive of Roma Enslavement.” PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 139, no. 5 (2024): 872–76. https://doi.org/10.1632/S0030812924000701.

Hartman, Saidiya. “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008): 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-1.

Mudure, Mihaela. “Blackening Gypsy Slavery: The Romanian Case.” In Blackening Europe: The African American Presence, edited by Heike Raphael-Hernandez. Routledge, 2012.

Necula, Ciprian. “The Cost of Roma Slavery.” Perspective Politice 5, no. 2 (November 2012):33-46.

Rovid, Marton. “From tackling antigypsyism to remedying racial injustice.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45, no. 9 (2022): 1738-1759.

“Sclavia Romilor în Țările Române (The Slavery of Romani People in the Romanian Principalities).” The National Center of Roma Culture. https://web.archive.org/web/20170616230112/http://ro.sclavia.romilor.ro/.